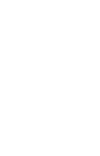

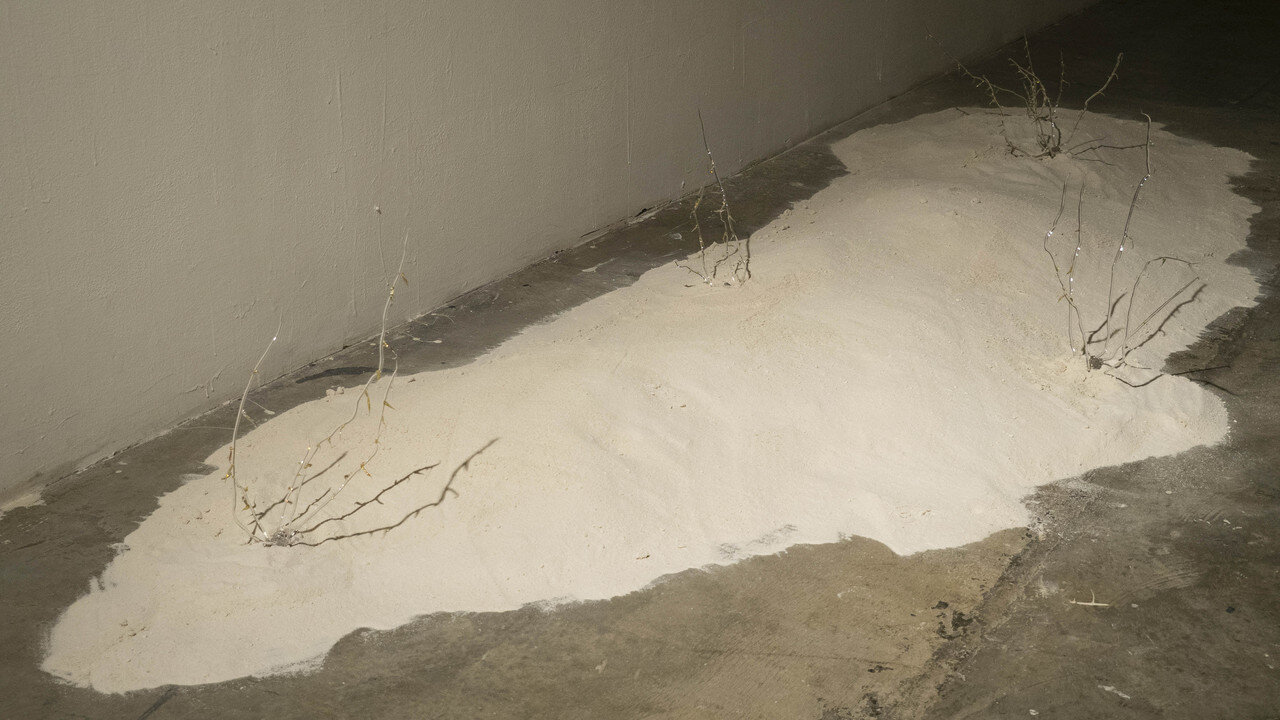

Joey Enríquez (b. Simi Valley, CA; lives and works in Washington, DC.) makes prints and sculptural work that consist of clay monotype prints and digital renderings about location, movement through space, and the passage of time. Enríquez earned their B.A. in Art–Design from California Lutheran University (2018) and their M.F.A. in Fine Arts at the George Washington University (2020). Originally a graphic designer from Southern California, they transitioned from design to art in 2017 to explore a more interdisciplinary creative practice. Their most recent exhibition, desierto desierto at Gallery 102, unearthed family narratives and revealed erasure of indigeneity in the southwest deserts.

Artist statement

In my work, I investigate erasure of memory and experience, environmental decay, and movement through lineage across temporal spaces. I explore the effects of generational trauma and the development of contemporary social relations by looking to archives and catalogued narratives. My own movement through space is essential in the development of the sculptural objects I build and the prints that I create. I warp the site-specificity of each object and installation in order to create friction between the linear thinking of the canon of recorded history and the reality of the spatial relations we establish. Disrupting fact and fiction, past and present, I point to power dynamics, such as race, gender, and environment, that have been put in place to silence marginalized experiences and endanger the future survival of silenced identity and experience.

With my most recent sculptural work, I questioned the record of my maternal family history and the erasure of their, and subsequently my own, mexicanx identity. Through adapting and altering the process of adobe brick making, I fabricated a sculptural ruin, "if you cant find your own, store-bought is fine" (2020), based on the real ruin of a wall at my great great grandmother?s property in New Mexico. Here, the murder of my great great grandmother and one of her daughters had been lost in time?while a newspaper article recorded the event, it remained unspoken about by future generations of my family after assimilating into white American society. Mostly relying on the abstraction of my own memory as time passes, I constructed and stacked each brick with a sense of desperation. I became compelled to forge a ruin before my memory faded and became no longer legible. Juxtaposing a murder with a captivating, monumental ruin-like adobe wall fragment, I emphasize the invisible acceptance of glossing over traumatic histories of oppression, cultural death, and erasure of identity in my work.